The Smallest Box of All

“Yeah, but why did you

bring that here?” The voice belonged to an elderly woman and was spitting like

fat from broiling meat.

“I didn’t get time to post

it. And it was raining. Rained every day. Don’t have a coat. Well, I do, but I

would’ve had to wash it.”

“You did wash it. I saw

it. On the line.”

“Ginny had filled the

pockets with nails. I don’t know why you let him borrow it, to be honest.”

“I don’t. He just takes it

when he’s working in the area.”

“Holes in the pockets. And

a smear of what looked like dog shit down the front. It’s my coat.”

“Yes, but why bring it

here?”

What the oversized woman

with damp looking straw hair was referring to was a small box, about an inch

deep and the size of a postcard. She had withdrawn it from a suitcase that had

been carelessly dumped on a rickety looking single bed, one of two that she was

planning to shove together to make a double.

Although it looked

doubtful it would be able to support her weight.

She waved the box at him.

“Why does it smell so bad?”

“I might have put too much

stool in it.”

“Did you read the

instructions?”

“Yes. Put some stool in

the box and post it.” The man, who seemed bad at lying, snatched at the small box. “Give

it here, I’ll walk down to reception and post it now.” He would’ve added

something along the lines of ‘since it offends you so much’, but had stopped

bothering to argue with his wife a decade ago. It was pointless, and he didn’t

care enough.

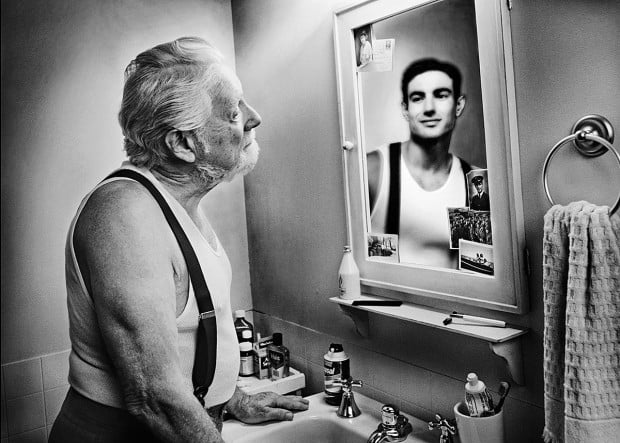

She was sixty next week,

and he spent that inky time between closing his eyes and plummeting into sleep

wondering how much longer.

“Grandad, Grandad! They got

two pools here.” A twelve year old, blonde boy had shoved his head through the

door of the static van.

“Have they?” Grandad

grinned, reached over and ruffled the blonde mop.

The boy pulled his head

back. “Don’t,” he protested.

“You never minded when you

was younger,” the older man replied.

Both walked down the steps

of the decking, erected so families could sit outside in the French sunshine

and get bitten by the evening wildlife that lurked in the bushes, waiting for

dusk.

Absently, Grandad reached

for the boy’s hand. The late afternoon sun was blinding. They were dodging electric vehicles and

bicycles, staffed by young attendants dressed garishly in pink who shouted

‘bonjour’ aimlessly as they passed from behind or in front and also there were cars stuffed with boxed in families, crawling at low speeds, blocking passage.

As before, the boy

grinned, snatching his hand back.

“You never used to mind

when…”

“What are you posting?”

The boy asked, ignoring him.

“Oh, it’s my stool sample.

In case I got bowel cancer.”

“What’s a stool sample?”

“Poo-poos.”

“That’s disgusting.”

“Yes, I suppose it is, in

a way. Smells a bit, too.”

“That’s why Grandma was

shouting.”

“Grandma’s always shouting,

Harry, if you hadn’t noticed. You get used to it.” They had reached reception

by now; a short walk. A blue sign proclaimed it so in French. But it looked a

bit like English, so that was all right. Underneath, also in French, a message

reminded the unwary that ‘reception closed at 7pm’.

Grandad pointed this out

to Harry. ‘Probably so the staff can drink cocktails and snog each other.’

Harry sniggered. “I don’t

think so, Grandad. It said they do entertainments in the evening.”

“Bollocks to entertainments.”

And the gate that allowed

cars to enter and exit was also locked at 11pm. So mote it be.

Grandad entered reception and was ticked off straight away that it was staffed by two very young looking,

trendy individuals, one of each gender. Neither was in a particular hurry to

offer assistance.

Eventually, the

pony-tailed male looked up from his phone, assessing Grandad with ennui whilst

Harry wandered around looking at various leaflets and flyers. “How may I help

you?” he asked, in reasonably good English but with a thick, French accent.

Grandad wondered how he'd guessed. To speak it. English, that is. “Je vouderay un poste la cadowe blonc avec

Angleterre.” he replied, in his very best French. “C’est un…er…stool sompul.”

“What?”

Grandad blinked. Harry

tittered, joining him at the desk.

The young man reached for

a biro and pad of paper. “Your name, sir?”

“Juh ma pel mon-shoo-er

Paul.”

“Mister Paul. And what is

the number of your accommodation, Mister Paul?”

Grandad couldn’t remember

the French for 105, so he waved his smelly box at the young man. “Juh aim-ay luh

bu-wat dans luh pohst.”

“I see. You want me to

post this box?”

“Ah-wee.”

Taking the box, the

attendant finger and thumbed it with distaste, no doubt noticing the unpleasant

stench, glanced at his colleague and said something rapid-fire in French, that

neither Grandad nor Harry could follow.

Paul did a pretty decent

mime of someone taking a box, and putting it into the slot of a letter box,

just to be on the safe side, while the receptionists watched impassively. “You

see, Harry? I should be on the bill for the entertainments tonight.”

“You should, Grandad.”

And, satisfied, both left

reception, ready to do a bit of exploring.

“Good French, Grandad.”

“Thank you, Harry.”

It was the next day. Paul

had spent some time in the toilet.

The previous evening,

Grandma and her daughter, Harry’s mother, had dragged them to the bar where

unadventurous types sat outside and munched on the overpriced food that the

young employees churned out from freezers – hot-dogs, burgers, pizzas, chips

with cheese on them, bags of warmed up Doritos with yet more cheese grated over

the top.

“This fare is not fair,”

remarked Grandad, upon receiving some congealing pasta, and waving the receipt

at Harry.

“Shut up, Paul.” Grandma had replied. "You're not funny."

“Sorry. I was worried it

might give me bowel cancer.”

The animateurs had stood

on a makeshift stage, dressed in pink and white, fronting them with a laptop,

speaker, microphones and had jumped up and down to Eurodisco hip-hop with a samba beat for

two hours, blowing whistles, whooping and hollering French into the night. It

had been ghastly.

Now, however, the sun was

only just rising above the tips of the pine forests and casting long splinters

of light across the dew soaked metal tables and chairs. The whole site was

asleep of course at this early hour, save for a tousle-faced old man pushing a

broom amongst the furniture, gathering up the previous night’s trash.

Paul had used tissue to

wipe wet from the chair he was sitting at, scribbling into a small notebook.

Occasionally he scored through some words or lines and rewrote them, sipping

cooling coffee from a tin mug he had prepared in the kitchen.

Once the coffee had

finished, he shook drips onto the floor, shouldered his rucksack, wandered back

to the static van, which was quiet, and left the mug on the steps.

Still early. Hours before

anybody would be stirring. What to do?

He walked reasonably

briskly to the locked gates by reception – he wasn’t getting any younger – and

read the French signage. One fingerboard pointed to ‘La Plage’, which he

remembered was beach and the sandy road led up a small hill towards a windsock

which hung limp.

As good a way as any.

Cresting the dune and

disliking the way the feel of sand was making his teeth itch, he lolloped down

the other side.

It was quite lovely, the

way the glassy Atlantic lapped the yellow bay,

stretching in crescent to the left and right as far as he could see. It was

only punctuated by occasional off-white apartment blocks on the tops of jutting

crests. In the very far distance, he could see two seaside towns – one left,

one right – which he was sure he would visit to look at markets. He found out

these were La Croix en Vie and St Jean de Monts.

But that was later. Once

he’d purchased a map.

Paul was summarily

interrupted. “Excuse me? Do you know the way to Bordeaux?”

A man, perhaps ten

years older than Paul, with an English accent and possessed of an embarrassed

tone, whose grey beard and draggled hair were missing scissors, was balancing on a

bicycle, possibly blushing.

“I seem to have come off the

coastal path,” he added, dragging out a weather-beaten map from his rucksack

that looked to be one of those given out free on ferries.

Taken aback, Paul rubbed

his stubbly chin, for it had been too early to shave as yet in fear of waking

Grandma and getting pelters. “Er…Bordeaux…well

it’s a bloody long way from here, I think.”

“I’m cycling there.”

The voice was familiar, as

was the posture. Paul looked more closely at the rucksack strapped to the old

fellah’s back. “I’ve got that very one.”

“I know.”

“How?”

“I can see it.” The

cyclist wobbled a little, stretching out with his left heel and toes.

“You should adjust the

seat.”

“Saddle.”

“Yeah, I know.”

“Well?”

“What?”

“Do you know the way to Bordeaux?”

Paul pointed to his left,

because that was towards the south. “That way, probably. Why do you want to go

there, anyway?”

“It’s for the adventure,

isn’t it?” He looked about to remount and set to, but before he did, he

remarked. “You know, I was here before. Nice place, this. There’s a bar over

there where they do cider. You sit outside and there’s some nice entertainment.

Sweet. The cider, I mean. See yah.” And with that, he was off.

Paul shrugged and set off

to the edge of the sea, determined to paddle in it.

It was almost completely

deserted, except for two or three dog walkers and a few people out for an early

morning jog. As he reached the water, he turned towards Bordeaux and began walking through the gentle

waves. It was cold, but welcoming after the initial shock, save for the sand

between his toes, which Paul had never liked. Reminded him of gritty

sandwiches. The bread soft, the butter melted, the cucumber warm, the texture

crunchy.

The thought made him

shudder, taking him back to a cold, grey Cleethorpes.

Or worse, a thin day at

Oxwich on The Gower, where he’d lost his bucket and spade, aged four. His

mother had made him stand at a gate for what seemed hours, asking every

stranger: ‘have you seen my bucket and spade?’ One said they had, was it red

and -- if so - it was just beyond the dune in a little stream, full of sticklebacks

that a crab was eating.

After half an hour, Paul

had remembered his bucket was blue.

Still, this beach was

unspoiled, and before long he had walked a mile or so. In fact, coming the

other way, a middle aged woman, of long grey-blonde hair and promising smile had

splashed past him, holding sandals in her left hand.

Paul smiled back: “Ah,

that’s it.” And he kicked off his own sandals and continued bare foot.

When he reached the first

outcropping of apartments, he turned left and walked back up the dunes. With

every step, his feet sunk into the sand and impeded progress; by the time he

had reached the top he was panting and then there was a 500 metre band of pine

forest to negotiate. The wide wooded path led him to the road, busier now – he

turned left again followed the cycle path back to where he had begun.

The road snaked its way

alongside and after twenty minutes he could see a queue outside the boulangerie

and could smell freshly baked croissant; buttery and seductive. Paul

realised he was quite hungry and checked his phone. 8.30 already.

A sharp bell made him

jump.

“Watch out.” A familiar

voice shouted. Wobbling towards him, the old man, still making his way to Bordeaux with steely

determination. Paul watched him ease past, noting that the more pronounced

instability could be because in his right hand he was holding a baguette,

wrapped in brown paper. Occasionally he would rip his teeth into the hard

crust.

After he had rounded the

corner and Paul could see him no more, he crossed the road and joined the

queue, feeling a pang of something – pity, envy, nostalgia?

“Cycling. That’s the

thing,” his brain muttered, then adding ‘that will catch the conscience of the

king’ without any reason to. Except it rhymed.

Those feelings didn’t last

long. Paul stuffed bread into his rucksack and made his way back to the static

van. It was still silent.

Maybe an hour later, there

was movement.

Harry had left his room –

or rather that portion of the van that was separated by thin walls into his - and

had sat on the L shaped couch against the external wall, thrown a blanket over

his head and was playing with an electronic game. He’d be there until ordered

to brush his teeth.

Paul didn’t say much aloud

because it always caused arguments and unpleasantness from either or both of

the two women and the defensive effort wasn’t worth the play. These days he

just let the goals in.

Instead, he jabbed the

heap under the blanket with his right hand approximately where Harry’s midrift

was, then, as quietly as was possible, given the creaking floors and decking,

started to lay the outside table for breakfast. Pretty decent, he thought.

Yoghurt, apple juice, French bread and jam, some strong smelling cured meat and

cheese.

Looked alright. Years ago,

in previous lives, he’d always enjoyed camping in France and knew the sorts of foods

to pick.

He wandered back inside

and switched the kettle on for a second coffee, thinking about the old man on

his way to Bordeaux.

“Bloody noise in there,”

snapped someone deep from within another space and time, “trying to sleep.”

Harry’s face appeared from

beneath his blanket. “Grandad, Grandad. What shall we do today?” He repeated

the name playfully, loudly, because that was how it had been growing up.

Grandad this, Grandad that.

Endless questions from the

backseat of the car during long, hopeful trips. But, no more. Paul guessed that

he’d answered most of Harry’s questions satisfactorily, for now. Treasure these

days, Grandad. Girlfriends were coming.

“Well, we’ll have a recce.

See what’s what.”

“Can we play football?”

“Of course. Definitely

football.” Paul wondered where, given all the traffic on the road outside the

van.

“Swimming?”

“That’s a fixture. There’s

a great beach, too.”

“Have you been to the beach?”

“Yeah. Had a walk this

morning while you were sleeping.”

“Why didn’t you wake me?”

“Because you never wake

up, tell me to push off and then your mother gives me pelters for making a

noise.”

“Yes.”

“I’ll be back in a bit.” He’d

heard stirrings. Not wishing to invade privacy, Paul took his coffee outside

and wandered the 100 yards or so to the bar area. There were a few more people

now and the sun had dried the seats – he sat down and sipped coffee for the

twenty minutes or so he supposed it would take, occasionally catching the eye

of other campers and offering a thin, neutral smile.

The old man was still

sweeping, collecting stuff on a shovel, transporting it to a sack. He didn’t

look too friendly and Paul didn’t blame him, wondering when the young

animateurs would put in an appearance to do less strenuous work like

aquafit class or kid’s club.

Who cared?

At breakfast, the two

women talked about the day ahead, tossing the odd barbed hook in Paul’s

direction which he dodged. They found the food acceptable which was a relief,

but, hadn’t slept at all.

“The bed is too small.”

“Did you hear that noise?

All bloody night.”

“Grandad’s snoring. It’s

atrocious.”

“I’ve been bitten. Bloody

mosquitos.”

Thoughtfully, Paul cleared

away the dishes. There was a dishwasher; he ignored it – they never did a good

job unless you washed to stuff before loading them – which rather defeated the

point.

“Why are you doing that, you

bloody idiot? There’s a dishwasher.”

“So there is.” Paul

finished rinsing the plates then loaded them into the machine. “Harry? You

understand these beasts. Work some magic – make it go.”

After which, both packed

rucksacks and escaped down the steps, into the wild, blue yonder.

“Where shall we go?”

“Did you put your trunks

on?”

“Of course I did,

Grandad.” Harry grinned and thrust a blue football in Paul’s face, making him flinch.

“Naughty boy.”

Harry bounced the ball and

trapped it with a nimble foot, tapping it sideways and behind so it reached

Paul’s left foot. He returned it, not quite so skillfully, and in this way they

ambled towards reception, cursing when it became trapped under cars.

The big pool, with all the

slides, rapids, spas and so forth, was opposite reception and parallel to the

road. In this way it could catch the attention of passing cars, working to

advertise pleasures of the site. However, all the competitors did the same and, driving

by, Paul’s vision was assaulted by various garish cartoon structures, rising

and twisting aloft alongside rickety looking metal steps like ladders that

Jacob might be careful to avoid.

“There’s the pool.” Harry

picked up the ball.

As they had walked the

very short distance from the van, they’d passed several families proceeding in

the same direction. There was generally a dominant male at the head, but sometimes

a female, whilst other members followed behind. You could tell the leaders by

the way they were pulling medium sized trucks on four wheels with their large

handles.

Inside these trucks were

piles of towels. Some inflatables, the occasional bag, but, by and large, huge

piles of towels. Stitch all these together and you’d have many coats of many

colours.

Paul groaned. The gate of

the pool was locked and, leading from it was an enormous line of people waiting

with their boxes on wheels. What was it with the trucks? Paul hadn’t done a

holiday for a couple of years and he thought this must be a new thing.

He noticed how, when trends

happened, they kind of exploded and everybody had to follow, then, like fireworks, they fizzled

out. In the 90s there’d been a run on those huge picnic boxes with collapsible

handles. Before that, everyone was taking candles to parks with spikes you

could drive into grass.

He doubted that

these trucks were a either a good thing or a sign of intelligence.

Instead of waiting, Paul shoved a truck aside, ignored the protests and marched to reception, Harry in tow. As it were.

As they entered the box, the

same pony-tailed young man was in attendance, not looking as if he’d had much

sleep. Possibly he’d been on stage whooping ‘wee-wee’ loudly, jumping up and

down and blowing whistles until midnight.

Paul rapped the desk with

a Euro, a little rudely. “Oo est lez…er…trucks?’ he snapped.

“Do you speak English?”

The young man sighed, clearly in no mood for negotiating very bad French,

spoken loudly.

“Of course he speaks

English,” replied Harry, “he's a chunky monkey.”

“Don’t call me that. This

is my Grandson.”

“Sir. What do you want?”

Paul could see the

receptionist was doing his very best to be patient, so decided to push him a

bit, realizing that his irritation and resentment towards the campsite was

building a little. “Do you know about these trucks?”

Shaking his head, the

young man admitted he didn’t.

Co-opting Harry into his play,

Paul lay on his back and put his arms and legs into the air. “Drag me around,

Harry.”

“But you don’t have

wheels.”

“True.” Paul stood up and

once more rapped the desk. “Do you have any?”

“What?”

“Wheels.” Paul started to

do his very best mime of someone dragging a truck full of towels around some

winding lanes, occasionally mopping his brow and looking up at the angry sun

overhead.

“Grandad is a drama

teacher.”

"Is he?"

“As well as other things.”

“What other things?”

Paul smiled winningly at

the receptionist, who looked about to explode, particularly as two or three

other punters had, by now, entered and were looking on in bemusement.

Turning to them, Paul

remarked. “Those trucks. They’re all over the place, getting in the way, the bloody things.”

The woman behind him

nodded unpromisingly. “Yes. Where do you get them?”

Paul glared, Harry

tittered and both turned back to the receptionist. “Why is the pool not open?”

“It opens at 11, sir.”

“No, no, no,” snapped

Paul.

Tapping him on the

shoulder, the woman asked, “Are you going to be much longer?”

“I’ll take as long as I

want,” Paul replied. “Thank you so very much.” He turned his attention back to

the young man. “Not when, why? The pool should be open early doors. What if I

want an early morning swim? You know, get some exercise before la pi-tee

de-journay.”

“If we open, there are

complaints. People put towels on all of the loungers.”

“What about my early

morning swim?”

“Go to the beach.” The

receptionist moved to the woman who seemed entirely content with the situation.

“How may I help you, madam?”

Thus dismissed, Paul

followed Harry back to the pool – or rather to the end of the line of trucks,

noting that it was only 10.30. He now noticed that the queue consisted of

leaders only. Other family members had dispersed themselves to tables, watching

the clock like vultures.

Paul could take no more.

He tapped the man in front of him on the shoulder. “What is all this?”

“Got to get here early,

son, if you want them sun-loungers for the day. I got to get these towels on

them. It’s a right scrap. Especially on a sunny day.”

Not waiting to see how

campers could get those trucks through the small gates that led into the pool or wanting to see a battle over deckchairs and swearing under his breath, Paul took Harry out of the gates.

They walked up the hill he had previously climbed that day.

The beach was mostly empty,

vast and expansive.

The day of Grandma’s

birthday dawned.

By this time, Paul had

settled into a routine. He had become a man of routine – perhaps he always had

been, he couldn’t remember now. It was one of many reasons he had resisted

holidays abroad.

There was a certain safety in routines,

however. It avoided conflict whilst being scrutinised by baleful eyes – as the

Martians had surveyed the Earth, before drawing their plans against us.

Just so.

Get up early –

for Golden Time – sunrise, a long walk, the notebook, the waves against the

beach and then back to the chores. His wife and daughter, once fed, tended to

stay in the static van, spreading themselves across cushions like pancake

batter, complaining as the sun crisped their edges. This left the rest of the

day for time with his Grandson, which they were making full use of.

Today, however, Grandma’s

birthday. A big one too. Bloody 60. Another reason why he’d paid for two weeks

in France.

At the outset of the

vacation, he’d bunged that permanently ireful and unhappy soul a heap of pocket

money as her present and put a birthday card between the leaves of his diary.

But he dare not risk it. Discretion is the better part of valour and all that.

So, taking sensible

precaution, he had whipped into the supermarket next door – that sold plenty of

‘Produits de Vendee’ – and bought a dozen or so of the best looking ones,

wrapping then in a none too cheap linen bag emblazoned with ‘J’aime La Plage’.

Thus armed, he had

prepared breakfast, offered cake and presented these with a gritty smile.

To his relief, they had

been received well. As had his plan to drive to La Croix En Vie and visit the

local market.

Her daughter had noted,

two or three days ago, that there was usually a market in one of the several

small towns within reach of the campsite. In different places on different

days. Paul supposed they were the same vendors but that they cunningly

relocated. After all, they had a living to make.

So, the morning had passed

without much of a hitch.

Paul watched the two women

hobble around for an hour, buying merchandise, walking a couple of paces behind,

in case one of them toppled over, but also to avoid upsetting either by doing

something deemed inappropriate – and getting shouted at.

In fact before lunch, he

had only been snapped at once. A pretty severe incident, but miraculous in its

way that it was one of a kind.

Harry had discovered some

stall or other. Paul shambled behind, singing to himself, a tune that had

lodged itself into his brain that morning on the beach. Something by Electric

Light Orchestra: ‘Mr Kingdom, help me please…’

”Look at this Grandad. Can

I have some Euros? Please, Grandad?”

“What the bloody hell is

this, Harry?”

In front of him? A shifty

looking bloke, wearing a beret and a table full of boxes wrapped in grey

plastic – next to which was an electronic weighing scale and a piece of

cardboard with ‘2 E’ scrawled in black marker. The man was almost doing a

roaring trade, too. Three or four punters had paid and carried away packages

with smiles.

It was a mystery, that’s

what it was. To Paul, anyway.

However, it appeared Harry

had been watching for some time and had got the gist of it.

“We have the same in England.”

“We do?”

“Sure. These are all

unclaimed packages from the Post Office. You pay money and take one. You never

know what’s going to be in them.”

“You don’t?” So it really

was a mystery.

“It’s great, isn’t it?”

“Possibly.”

“Yeah. Someone I know got

an I-Phone.”

“Indeed.”

“Oh, come on, Grandad.

Give us some money.”

“Well, if it’s only two

Euros, I suppose.” Paul reached deep into the back pocket of his jeans and

produced a few coins which he passed to Harry. There was a catch, however. The

weighing scales. It was two Euros per unit of weight.

Too late.

Harry raised his eyebrows winningly,

grinned and took a couple of notes from Paul, trousering the coins for good measure.

He took, from the table, a medium sized box, had it weighed, and, some time

later, was back with a pitiful handful of leftover coppers.

By this time, the two

wheezing women had caught them up. “What has he got there?”

“Yes, what are you wasting

money on, idiot?”

“Yes, what a load of crap

that looks.”

“Yes, can’t let you out of

sight for more than two minutes.”

“Yes, not more than two

minutes.”

“Yes. Time we went back to

the campsite.”

“Yes, before any more

money is wasted.”

Ignoring them both, Harry

eagerly tore open the plastic packaging, passing the trash to Paul, who hastily

scrunched it up in his fist as if in vain to hide evidence from plain sight.

The box was next. Divested

of all disguise, the inners were revealed. “What are these?” muttered Harry,

holding up the contents in ill-concealed disappointment. In his hand were

several pieces of plastic, coloured orange.

“I think they’re clamps,”

Paul replied, taking one and holding it up to the light, critically.

“Clamps?”

“Yes, clamps. The sort

that workmen use to hold pieces of wood in place on a workbench. Very useful,

actually.”

“If you’re a workman.”

Harry pouted. “I’m not a

workman.”

“No, he’s not, is he,

Grandad?”

“No, he’s not a workman,

is he?”

“No, neither of you are

workmen, are you?”

“No, neither of you are.

And you never will be. What a waste of money.”

“Yes, a complete waste of

money.”

“How could you be so

stupid?”

“Yes, how could you?”

“Go and get his money

back.”

“Yes, go over there and

demand his money back, idiot.”

But another sign,

previously unnoticed, in French, but readable, warned the unwary punter that

there never was or would be any money back. “Them’s the breaks,” Paul muttered,

in an uncertain tone.

They had travelled back to

the campsite shortly afterwards, nether of the women wanting the promised

lunch.

“She doesn’t want lunch.”

“No, she doesn’t want it.”

“Take us back, please.”

“You’ve ruined her

birthday, now.”

The short ride had been

mostly silent, save for barbed protests if he’d taken a road bump too quickly

or hadn’t shifted into fifth sufficiently well. It had been a relief to pull up

alongside the static van and unload the baggage.

Now, later that day, it

had been decided to have a barbecue.

Each van was equipped with

an adequate gas fired barbecue. Their version squatted in the corner on the

decking like an elongated, metal frog – the mouth of which was the shutter that

pulled back to reveal the cooking surface.

Harry and Paul had been,

therefore, ordered to Super U Express to buy the necessaries and had spent a

fun time choosing skewers of meat, beef burgers, chops – doing their best to

avoid pork.

“I can’t eat pork.”

“Yes, she can’t eat pork.”

“Brings me on in a rash.”

“Yes, a rash.”

“You wouldn’t like that,

would you?”

“No, you wouldn’t like

that.”

He certainly wouldn’t.

There was plenty of lamb, anyway and Harry had pulled out some decent looking

steaks. They bought salad to toss, oil for fries and a couple of bottles of

fizzy wine.

“What’s that like,

Grandad?”

“Don’t bother – it’s like

sucking lemons.”

Now, back at the static

van, evening was drawing on, mosquitos were waiting for a barbecue of their own

and scores of families had passed in the opposite direction to the morning,

dragging their trucks behind them. Amidst the noise of spoilt infants screaming

and protesting that their day was over, Paul was chopping salad and warming the

fat for chips.

Harry had been looking

forward to being in charge of the barbecue. A bit of a man treat. As such,

several of the meat skewers were already on the grill, hissing pleasantly.

However, it was not to be.

The two women had

reluctantly pulled themselves heavily off their respective beds and had

shuffled through the door, blinking before the setting sun.

“Don’t go near that

barbecue.”

Harry looked at them with

disappointment. “Grandad says it’s OK.”

“What does he know?”

“Yes. What does he know?”

Then, one of them yelled

in through the door.

“You idiot, do you want

him to get burned?”

“Don’t you dare let him

get burned.”

And when Paul looked out

from the van, having finished the salad, Harry was sitting on one of the

chairs, safely away from the grilling meat. He had his hand held computer game

switched on and was engrossed. “Who’s minding the meat?”

Grandma looked at him from

her chair. “You leave that barbecue alone. You’re not fit to go anywhere near

it. Leaving a 12 year old boy in charge. You should be ashamed of yourself.”

“Yes, you should be

ashamed.”

“Leave that barbecue

alone.”

“Yes, leave it alone.”

“Don’t touch it.”

“Leave it. You’ve done

enough damage.”

Later, after he’d finished

clearing the dishes - washing them, then putting them in the dishwasher to be

on the safe side – Paul was scrubbing the decking where meat and oils had

dripped underneath. He decided that this was the last time he would ever take a

holiday.

He turned to Harry. “Hey,

mate. Why don’t we go cycling tomorrow?”

It was going to be a hot

day.

Avoiding the queue of

towel laden trucks by reception, Paul and Harry scurried through the gates early

doors, onto the quiet road that led into Les Mouettes and turned sharp left.

Maybe one hundred yards further up the road, still on the left, was a small

complex of three shops linked together, named for the small village, ‘Les 3

Mouettes’.

Paul had investigated

these shops earlier on in the week – nothing exceptional – inside were

souvenirs, T Shirts, ciders, wines.

But outside the middle

shop were bicycles for hire. A good variety, too. Several of those

multi-cycling vehicles, tandems and some bicycles that might be suitable for

the older gentleman. Wide saddles to save sore buttocks, that sort or

requirement. And swift velos for the more dynamic types, like Harry.

To be honest, Paul had

wanted to cycle but was worried his body might not be up to it. However now he

did not care. Body be damned. If some ghost-faced senior citizen could find his

way to Bordeaux,

munching on an old baguette, then so could he.

“It’s not open, Grandad.”

Indeed it wasn’t. There

were no bicycles outside whatsoever. Not so much as a pump. Which was a bummer,

really.

But, as all seemed lost,

the door opened and a middle aged woman appeared. The breeze caught her greying

bangs, which briefly curtained the lines of her face and the sun glinted on the

rims of her glasses. As she saw them, she smiled, a warm smile, a smile Paul

knew he could never forget.

And at that very moment, he

realised he was going to miss her forever.

“Allo. Bonjour.” She

walked towards them briskly, her chest, her loose buttoned blouse, her ankles, her

everything and that smile. Was she going to touch him? Were her arms going to

caress his back?

No.

Paul cursed his bad

French, which he had ironically nursed all these years for comic effect, wished

he hadn’t, but then shrugged.

“Avez-vous un salopette?”

She frowned but then

laughed. It was a good laugh, too. Full of real humour. She switched to

reasonable English. “How can I help you? We don’t open until ten hours.”

Somehow, Paul knew he was

winning, but blushed. He persisted. “Oui. Oui. Noo voodray lay duh bee-cee-clet

poor avec lay juh-nee donz lee forest…er…what’s French for forest, Madame?”

“Foret.” She laughed

again. “If you return in minutes thirty, I will bring you the cycles. Les

velos.”

Minutes thirty couldn’t

pass quickly enough. Harry and Paul sauntered up and down the two or three

streets of the small village impatiently, the scent of early morning baking

filling the nostrils, the gritty sand and gravel between the toes, the sweat

trickling down the back.

They returned well before

the allotted hour was due.

By this time, a large grim

faced man was humping bicycles outside from within the opened doors, fixing

them to racks in anticipation of the trade to come. He registered them, said

nothing and continued his task.

Uncertain of what to do,

Paul lingered outside while Harry inspected the bicycles, looking for one he

preferred.

“Don’t kick the tyres,

Harry.”

The woman appeared at the

door, dazzled Paul with a smile and strolled towards them. “You prefer comfort

or speed, Monsieur?”

Paul took a sharp intake

of breath. What? Good grief. He blushed and before he could say anything,

Harry pointed at his backside.

“He’s a chunky monkey.”

The woman laughed again.

She was so happy. So bloody happy. Paul, unused to happy people, laughed too.

“And you, Harry, are a naughty little boy. I will punish you most severely for

such a thing as that.”

Her eyes twinkled. “Your

son?”

“Grandson.”

“Oui. Grand-fils.”

Looking at Harry and

sizing him up, the woman spent a little time choosing a cycle that was about

his size, adjusting the saddle, checking his toes could touch the ground and

making sure it was a good one. Satisfied, she kicked the stand down with her

foot and rested it in front of the boy. Then, with a grin, she turned her

attention to Paul.

Her gaze travelled to his

backside. “This one,” she pronounced, choosing a cycle with a wide saddle. “It

is not so fast, but it is comfortable. I choose this one myself.” And her eyes

teased him, just a little more. She helped him mount.

“It’s perfect. C’est

parfait,” Paul spluttered, feeling his blood tingle at her touch.

She grinned. “Ah, so you

do know to speak French.”

“Not well.”

“It is nice that you try.” Her eyes twinkled. And with that, she beckoned them into the office for payment, so both Harry and

Paul followed behind.

Once inside, she took a

pen and a book of printed forms, starting to fill in details, leaning forwards

over the desk in such a way that Paul had to try hard not to look. “Your name? Your

address? Phone number?” She scribbled details quickly and took the payment,

laughing as he answered.

Paul scratched his chin.

Harry would need a safety helmet. But what was the French for something so complicated?

He considered it deeply for a moment, looking at the tip of her tongue,

slightly wetted between mocking lips, wondering if she could read his mind.

“Avez-vous un chapeau de securite?” he asked.

The woman roared with

laughter. “Casque.”

“Casca,” repeated Paul,

transported to the assassination of Julius Caesar for an instant.

“Casque,” she emphasized,

retrieving one from the wall and passing it to Harry. “And you?”

“No, I don’t need one, I

am old.”

“That,” she teased, “is

not a good reason.” But she let it go whilst passing them bicycle pumps, tyre

repair kits and locks. “Here is a carte. It has all the good paths through the

forest and on the coast. You will have a wonderful time.” It looked as though

she wished she could come, just for a moment. “Have a great day. Bon journee.”

As they were leaving, Paul

turned back to her, wanting something desperately, some sort of connection, a

permanence. “I’ve seen you before. On the beach.”

“Yes, I know.”

“You were carrying your

sandals.”

“Have a good day, Mr

Paul.”

And they did, Harry

tearing on ahead with glee, Paul puffing behind, both consulting the map and

stopping for ice creams and drinks as the mood took them.

It was the best day of the

holiday by a forest mile. And all the time they were cycling coasts or

shuddering over the bumpy sandy paths, Paul’s thoughts were drawn between the

woman and that old man, the one on his way to Bordeaux.

Later they returned the

cycles, but were received by the large humping man.

Paul had already guessed

this would be the case. He knew he was never to see the woman again.

A couple of days later,

Harry and Paul were swimming.

The second pool was

smaller, had no features other than a deep and shallow end and was lined by a

wall of trees and concrete. The sun got to it mid-morning. It was an outlier,

ten minutes of walk from the bar area and toilets and the Wi-Fi signal wasn’t

as strong. There were sun-loungers, but less than by the main pool and it took

more effort to drag them into clumps – if you were into that sort of thing.

Paul, who wasn’t, supposed

that this was the reason it was less busy.

The water was cooler too,

being slightly deeper – but not so deep you were in any danger. In fact from

the middle upwards, it was very shallow indeed.

A sign proclaimed that

‘there were no lifeguards’. But both Harry and Paul were good swimmers, given

the chance, and cared less.

They had arrived at the

appointed hour, waited for the gate to be unlocked, dumped a couple of towels

on a lounger and jumped in.

“First in the pool!”

Harry had a small football

which he threw, arrow straight at his Grandad, or, if he was feeling more

malevolent, bounced on the surface just in front of his head, causing water to

splash into his eyes. This game they played for twenty minutes, until Paul’s

arm was aching and his drowning ears full of water.

In fact, Paul’s tinnitus

was bad. Last night, because the two weeks were winding up, they had recklessly

gone to the bar, had a drink and watched the animateurs do ‘Rainbow Rockshow’.

After an hour of his ears

being assaulted, Paul had left. Largely because ‘Rainbow Rockshow’ consisted of

five or six cross-dressed teenagers shouting ‘wee-wee’ or ‘woo-woo’ to a looped

eurodisco hip-hop tape and jumping up and down blowing whistles.

To be fair, it had been

quite well received by the majority of campers.

But the crappy samba beat

was still ringing in his ears, so Paul crawled out of the pool and flopped onto

the lounger whilst Harry hurled the ball at him. Occasionally he would have to

get up and retrieve it if it bounced against the edge. “Here, old son. Can you

not chuck the ball at me for a bit?”

“Well, come back in the

pool.”

“By and by. My head hurts

and my arm’s a bit stiff.”

“That’s because your

throwing is rubbish. You need the practice.”

Paul had to admit it was.

“But, I’m an old man.” It was a feeble protestation, even as he heard it. He closed

his eyes against the sun because it was peaceful, save for the tinnitus

pounding ‘tum-ti-tum-ti, tum-ti-tum-ti’ over and over.

But then there was a

disturbance. A large rattling at the gate to the pool, a scraping of concrete

like nails down a blackboard, a splashing of feet in a footbath.

“Pull it harder, mate.”

“Yeah, you push, I’ll

pull, we can get these through, no worries.”

“It’s scraping the walls.”

“Bollocks to the walls.”

After about five minutes,

the first of what turned out to be three trucks appeared. They had been pulled

like a wagon train through the narrow passaged footbaths but had survived

intact.

The first two were heavy

with towel, the third had one of those picnic hampers and several large

inflatables – a frog, a horse, a canoe and several insubstantial looking giant

tyres. They had been pumped all ready.

Also pumped, those in

charge had been three men, pushing, pulling and forcing passage. The first was

skinny and wore speedos, the second had a tufty squirrel ponytail sprouting

from the top of his head, like a coconut and the third was fat, his flaccid

belly tumbling over the top of his shorts.

All of them were pasty

looking and spoke in fluent Estuary. They clearly liked what they saw

“Sound. It’s empty.”

“Get them towels all

about.”

“Got yah.”

Fatbelly took armfuls and

carefully laid them on a dozen or so loungers that had not yet been claimed.

“That about right?”

“Yeah. Just put a couple

more, in case.”

And with that, they left,

having accomplished what they had set out to do.

Paul bristled and was

almost tempted to take the towels, toss them over the fence and puncture the

inflatables and wagon tyres. Instead, he returned to the pool to play ball. But

his mind wasn’t really on it. For no reason at all, he felt irritated and

invaded.

If Harry felt the same, he

wasn’t saying. He continued to throw the ball, challenge his Grandad to races

or swimming underwater, skilfully avoiding a handful of other swimmers who had

arrived before the wagon train.

Maybe an hour later,

Fatbelly, Coco-nut and Speedos were back. This time, they bought with them some

other stuff. Kids who screamed and bit each other over arguments about inflatables,

sour-faced wives in micro-bikinis who wore sunglasses, smeared sun-creams on

red flesh and stared oblivious into mobile phones and vapes.

Coco-nut and Speedos slumped back on loungers, sucked on vapes, exhaled

fruity-thick sickly fumes and began a long, interminable and loud discussion

about some other bloke ‘back ‘ome’ who they didn’t like and wasn’t present.

Never would be. Good thing, too. Arsehole. Of the first degree. And twat to boot.

Fatbelly had other ideas.

“Oy! Oy!” He had snatched one of the inflatable tyres off a kid, who protested

with a shrieking scream. “Bet you I can dive through the ‘ole in this tyre.”

None of his party was

interested, though. The two men continued vaping, the women continued staring

and tapping, the kids continued biting.

“Oy! Oy! Watch this. I bet

I can dive through this tyre. No problem.” And he slung the tyre onto the

surface of the pool, upwards of the middle.

Still nobody in the

lounger party looked.

Paul, however was vaguely

interested. He used a backstroke to push himself away from the centre, to the

deep end. Backed himself against the side of the pool. Pulled Harry with him.

Several others from the opposite ends of the pool were also watching curiously.

It was the sort of thing he'd have done himself, ten years ago. He could picture it like yesterday. But maybe not in the shallow end.

Fatbelly’s mates were

still oblivious.

“Oy! Oy! Watch me. I can

dive through the centre of this tyre. Piece of piss.”

Nothing from Speedos or

Coco-nut.

But Fatbelly was aware of

the other swimmers looking in his direction as he pranced up and down the edge

of the pool like a ballerina, his flesh undulating as a baggy trampoline with

loose springs might. “Watch this!”

With as much grace as he

could muster, Fatbelly plunged through the centre of the tyre, head first. The

dive was, it has to be said, pretty good, any splash being contained by the

tyre’s buoyancy. But then? Silence.

Paul screwed his eyes up

to peer from his distance into the heart of the pool. There was no

instantaneous surfacing. Just an eerie calm. Even his tinnitus was silenced.

But it probably seemed to

last longer than it actually did, before the storm came.

Fatbelly burst from

beneath the tyre, clutching his face, waist high in water. Blood was streaming over

his lips. “I’ve broken me fucking nose,” he screamed. “Me fucking nose. It’s

broken.”

The blood was quite

impressive, cascading into the water. Paul pulled Harry to the steps and they

clambered out. He gathered their things and didn’t wait to see what happened

next.

“Best we leave now, eh?”

“We could help.”

“There’s loads of them.

They’ll know what to do. We’ll only be in the way.”

“Yes you’re right, I

suppose.”

“Still, something for the

diary tonight, Harry.”

He could just imagine the

oncoming logjam of the three trucks in the footbaths, amidst towels,

inflatables, and flapping animateurs as some ambulance arrived. As well as the

cries of anger as Coco-nut and Speedos wondered how best they could sue the

campsite.

How to make sense of it

all? How could each splinter of ice be moved into correct positions and spell

out a word, a name?

Paul had been gifted one

quiet evening prior to departure whilst Harry had frolicked around inside one

of those arcades with slot machines and cuddly toys. He’d sat in Cave Des

Marines with a sweet cider that the large, friendly woman who ran the place had

recommended called ‘Cidre Doux’. Refreshing with only a little alcohol, he’d

sipped two and pushed a biro across his diary, watching the sunset streaking

the off-white buildings.

He’d wondered if this was

the very drink that the old man had recommended before continuing on his trek

south. He knew it was. And then his thoughts would drift to that woman who’d

struck his heart dumb – just for a moment.

His pen had scribbled

quickly. Recording how, that afternoon, Grandma and her daughter had required a

second visit to the market and Harry had been drawn to the man with his mystery

boxes.

Paul had scowled in his

general direction. He had still been wearing the grubby beret, the same sign, and

the same collection of grey packages.

“Come on Grandad.

Something to open on the ferry.”

“No. No more big ticket

items for you.”

“Just a small one, then.”

“Could be an I-phone.”

“Or ear pods.”

“Definitely ear pods.”

And with that in mind,

Paul had insisted that they buy the smallest box of all.

Now, he looked up, his

memories interrupted. Harry was pushing his way past a line of diners who were

queuing for breakfast on the ferry from Roscoff back to Plymouth. Having driven across North West

France, they’d had the good fortune of boarding early.

“The shop isn’t open yet.”

“Well, I told you it

wouldn’t be, didn’t I? They won’t open it until we sail, Harry. It’s to do with

customs and duty free. Where’s Grandma and your mother, anyway?”

“They’re queuing up for

breakfast.”

“Ah, of course they are.”

Harry threw himself down

on the sofa, beside his Grandad, grinning. “What shall we do, then?”

“You hungry?”

“No.”

“Not hungry. Well, you’ll

have to be a good boy, anyway. It’s quite a long trip.”

“Can we open that mystery

box now?”

The smallest box of all.

It was in Paul’s rucksack. A treat for when they were bored and could think of

nothing else. Obviously when Grandma’s attention was elsewhere, to avoid

unpleasantness. “No, I said we’ll open it once we’re halfway across, didn’t I?”

“Yes, but Grandma isn’t

here right now.”

This was true.

Paul, knowing he was

beaten, took out the grey wrapped box and passed it to Harry. “Go on, then.”

Harry snatched it and

ripped it open. His look of delight and anticipation switched itself off as

though there had been a power cut during the Miner’s Strike of 72. In disgust

he tossed the box at his Grandad.

Paul looked at it and all

those splinters suddenly fell into place. He knew what to do. The word was

spelt.

He held up the postcard

shaped box and shook it, gingerly. “You know what this means, don’t you,

Harry?”

His Grandson shook his

head.

“It means, my dear, that

I’m leaving France

with exactly the same shit I arrived with.”